Abstract

Within a time frame of about ten years, experimental

(interactive) media installations and performances have gained

recognition as new art forms in public space. Artworks explore the

interconnectedness of public space, interaction, and new media.

Urban Screens investigates how the growing infrastructure of

dynamic digital displays in urban space, currently dominated by

commercial forces, can be utilized in this context and broadened

with cultural content. The research project wants to network and

sensitize engaged parties for possibilities of using the digital

infrastructure for contributing to a lively urban society. The

integration of current information technologies supports the

development of a new digital layer of the city in a fusion of material

and immaterial space, redefining the function of this growing

infrastructure. Interactivity and participation will bind the screens to

the communal context of the space and thereby create local identity

and engagement.

Figure 1: New York Times Square: accumulation of LED boards.

Photo: Louis Brill.  The Redefinition of a Growing

Infrastructure The Redefinition of a Growing

Infrastructure

Public space is the city's medium for

communication with itself, with the new and unknown, with the

history and with the contradictions and conflicts that arise from all

those. Public space is urban planning's moderator in a city of free

players. [1]

Prof. Wolfgang Christ, 2000

How can the growing digital display infrastructure

appearing in the modern urban landscape contribute to this idea of

a public space as moderator and as communication medium?

The mobilization of digital technology and a growing

digital culture have changed the urban communication

environment. In the context of the rapidly evolving commercial

information sphere of our cities, various new digital display

technologies are being introduced into the urban landscape:

daylight compatible LED billboards, plasma screens exposed in

shop windows, beamboards, information displays in public

transport systems, electronic city information terminals,

holographic screen projections, or dynamic and intelligent surfaces,

integrated into architectural facade structures. [Fig. 1]

As McQuire has put it, "The migration of electronic screens

into the external cityscape has become one of the most visible

tendencies of contemporary urbanism." [2] Considering this

already existing digital infrastructure, it is a great challenge to

broaden the use of these "moving billboards," as Lev

Manovich calls them in his vision of an Augmented Space [3],

instead of flooding urban space with new techno-objects.

So far one of the main targets of this infrastructure is

to manage and control consumer behavior. We are not far away

from the implementation of technology that makes it possible to

cover buildings with large flexile planes of moving images,

networked and controlled from one central location but making use

of site-specifically collected consumer data. Display systems

already start to detect our behavior and adjust to our consumer

preferences.

Paul Virillio sees the new, developing "pervasive

architecture-style" of screens covering high-rise-facades as

"Electronic Gothic." [4] He refers to the narratives of

Gothic church windows, which where aimed at effecting people's

moral behavior. Immersion and its effects on the audience will also

be increased by the "perfect" incorporation of screens in

the architecture of the urban landscape.

How can the use of these screens controlled by market

forces be broadened and culturally curated? Initiatives such as

Locomotion, Going Underground, Strictly Public, Outvideo, the 59th

Minute and Transmedia :29:59 [5] are pioneering in their use of

commercial outdoor displays for screenings of video art. New

balanced alliances are needed that challenge city authorities and

regulators, architects, advertisers and broadcasters, as well as

cultural curators, artists, and the citizen as producer – joint

cooperations to shape the future development of the "screen

world" in a sustainable manner, considering the danger of

visual and technological pollution of urban space. [Fig. 2]

Figure 2. The range of screens in urban public space.

Urban Screens are defined as various kinds of dynamic

digital displays in urban space that are used in consideration of a

well balanced, sustainable urban society – screens that

support the idea of public space as space for creation and exchange

of culture, or the formation of a public sphere through criticism and

reflection. Their digital and networked nature makes these

screening platforms an experimental visualization zone on the

threshold of virtual and urban public space.

The Broader Context of Urban

Screens

Urban public space – understood as open, civic space

– is a key element in the development of European urbanism.

In this role as space for representation, culture, and encounter

through trade, exchange and discussion, urban areas have always

been a place that is rendered alive through various interactions.

Referring back to the old concept of the Greek Agora, urban public

space is a unique arena for exchange of rituals and communication.

A constant process of renewal and negotiation challenges the

development of urban society. The architectural dimension of urban

space has played an important role in providing a stage for these

interactions. Moreover, the architecture itself functions as a

medium, telling narratives about the city, its people, and the

represented structure of society. Its inhabitants can read the

reoccurring social interactions and the way the space is populated

in a participatory process. The whole urban structure is becoming

the crystallization of the city's memory over time.

Yet, the vanishing role of public space as place for

social and symbolic confrontation and discourse has been much

discussed in urban sociology over the last century. Sennett,

Häussermann, and Bott, in particular, have pointed out how,

since modernization, individualization and a growing independence

from place and time seem to have destroyed the old rhythms of the

city and therefore its social systems. We currently face a transitional

period of the restructuring of social networks and discover new

relations among people and places in a globalized world that is

threatened by diffuse and complex fears of instability and lack of

strong local roots. This situation has resulted in various

experiments with new types of relations, supported by developing

new media tools.

In its early stages, the Internet was discovered as new,

alternative public sphere. The rediscovery of a civic society is tied to

the inherent structure of the Internet, which is strongly based on

cooperative exchange and shared engagement through the

openness of systems. The population of virtual spaces –

virtual cities with their chat rooms, MUDs, and experimental spaces

for creating alternative identities – has been continuously

growing. Now we are looking at various experiments with

community in the growing field of social computing – peer-

to-peer networks, friend-of-a-friend communities such as Orkut or

Friendster, and, more recently, mobile communities connecting

mobile phone users. We also find participatory experiments in

content creation within the mailinglist culture and wiki and

blogging systems, serving an increased need for self-expression.

Now these explorations of virtual worlds have merged with the

rediscovery of urban public space, the recent popularity of locative

media being one indicator of this development.

In parallel, an "event culture" has evolved in

the real urban space. Guy Debord already foresaw "the society

of the spectacle" in 1967, and his critique of a society

"in which the individuals consume a world fabricated by

others rather than producing one of their own, organized around

the consumption of images, commodities, and staged events"

[6] should be taken seriously. In the growing international

competition among cities, the focus often is on tourism or the

citizen as consumer. City marketing and urban management

strategies are applied to create a vision of "creative

cities" that are in fact not necessarily supporting the

inhabitants' creative use of the city or their creative contribution to

a lively urban culture. Cities are engaged in a struggle with a

"feeling of placelessness" caused by the spread of

international architecture and branded shops. In fact, screens also

tend to look the same everywhere, so there is a need to consider

the locality as well as site-specifity of the content in order to

prevent further disconnection of the perception of our urban space

from the actual locality.

In order to maintain the social sustainability of our

cities, it is important to take a closer look at the livability and use of

urban public space and the rediscovery of a civic society. The

information platform www.interactionfield.de gives an overview of

numerous interactive media projects, assessing their potential for

urban society in terms of:

Promoting interaction, fearless confrontation and

contact with strangers

Promoting formation of public sphere by criticism,

reflection on society

Promoting social interaction and integration in the local

neighborhood

Supporting understanding of the current development of

our high-tech society

Supporting conscious participation in the creation of

public space [7]

Urban Screens can be understood in the context of a

reinvention of the public sphere and the urban character of cities,

based on a well-balanced mix of functions and the idea of the

inhabitant as active citizen instead of properly behaving consumer.

Virtual spaces alone cannot function as spaces for exchange and

production of identity.

The Character of Urban

Screens

In connection with the ephemeral yet open character of the

digital information world, Urban Screens asks for a new urban

language with its own dynamic signs and symbols, formed through

active participation from various players. New interactive

technologies and networked media offer more possibilities for the

visual programming of these digital surfaces through the interplay

of new display technologies, broadcasting tools, database and

content management systems, and sensor technology. Linda

Wallace sees "the internet as a delivery mechanism to inhabit

and or change actual urban spaces." [8]

Through the the Internet and other digital networks,

digital content has become more fluid, being, at least in theory,

available anytime, anywhere, produced for the audience of the new

global village. Could large outdoor displays function as

experimental "visualization zones" of a fusion of virtual

public spaces and our real world? Can we localize the huge flows of

information through these screens, and can these zones in fact play

a more active role, more active than just providing the canvas on

which the digital world is rendered? What characterizes Urban

Screens is a connection to the locality of the static nature of the

new screening infrastructure.

In contrast to the mobile screens integrated in phones,

PDAs, laptops etc., which display content for an individual, Urban

Screens focuses on the public urban audience, on joint and

widespread reception of media content. The growing

embeddedness in screen systems, accessibility of information via

Internet, mobile devices, etc. augments the respective urban space's

"situatedness." Levels of locality and globality vary,

ranging from the local neighborhood screens with symbols and

signs on a city level to trans-urban networks of screens enabling

new "glocal" interconnectivity.

Figure 3. Soccer game on the BBC Big

Screen in Manchester.

Visions of New Content and Use Visions of New Content and Use

The first steps in broadening the commercial

advertisement content of large digital outdoor screens focused on

the transfer and slight adjustment of TV features to the new

circumstances of public viewing. Soon we might have TV broadcast

stations specialized in urban public space and its local community.

The experiments done by BBC in collaboration with Philips and local

City Councils in various cities in the UK could be considered a

forerunner to these TV broadcast stations. They coordinated

outdoor movie-screenings, the collective watching of soccer-

games, and special City-TV news channels. [Fig. 3] Preferably set up

in key locations, in a setting for a wider audience, these screenings

in memorable places could support identification with local culture

through joint experiences. A local memory could indeed develop, if

the screens were used as a means for maintaining and supporting a

rich and complex local culture.

There has been a growing interest in connecting screening

infrastructure with cultural institutions that preserve and produce

digital content or video art. Cultural centers and institutions such as

the Schaulager in Basel and Austria's Kunsthaus Graz have started,

in a more experimental style, to officially integrate screens in their

architectural facades, so that they function as an extension of their

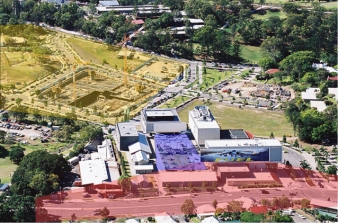

archives into public space. The Australian Centre for the Moving

Image uses the nearby public screen in Federation Square,

Melbourne. The Creative Industries Precinct (Australia's first site

dedicated to creative experimentation and commercial development

in the creative industries, located on the western fringe of

Brisbane's Central Business District) integrated three screens in its

complex of buildings to address different audiences. [Fig. 4] One of

the screens will be used to support the development of a new local

community in the vicinity. The above mentioned BBC project of

Public Space Broadcasting on community screens collaborates

extensively with local art institutions.

Figure 4. Orientation of the 3 screens

at the Creative Industries Precinct.

Sketch by Peter

Lavery.  A new audience can be reached on their daily routes

by bringing content into outdoor public space. Connecting Urban

Screens amongst each other could enable new mechanisms for

creating and maintaining relationships between cross-cultural

organizations and their audiences. A new audience can be reached on their daily routes

by bringing content into outdoor public space. Connecting Urban

Screens amongst each other could enable new mechanisms for

creating and maintaining relationships between cross-cultural

organizations and their audiences.

Connected screens could also serve as exchange

platform between the inhabitants of various cities. A repeatedly

suggested idea for using these screens is to enhance the

connectivity of remote communities through shared visual displays

that utilize videoconferencing. These connections between remote

spaces reflect the relativity of the terms "close" and

"remote" in a globalized world and an increasingly

transnational lifestyle. Hole In Space (1980), one of the early

projects of this kind connected the people walking past the Lincoln

Center for the Performing Arts in New York City with people in the

Broadway department store in Century City (LA) through life-sized

television images. The project Hole in the Earth

(2003-2004) linked the audience in Rotterdam with people in

Indonesia on the other side of the world through screens, camera,

and microphones in an installation resembling a well. [Fig. 5]

Figure 5. Opening of the installation Hole in the

Earth by Maki Ueda, Rotterdam, December

2003.

In Russia, China, USA, and South America large

networks are currently developing on a city as well as national level.

Screens become a key element in the government, regional, and

urban informational infrastructure due to their ability to easily

convey and spread content in local spaces.

The appeal of a local environment obviously is a highly

subjective matter, but a sophisticated social interaction and

information network in a local neighborhood could play an

important role in the perception of locality, supporting a feeling of

security. By connecting large outdoor screens with experiments in

online worlds, the culture of collaborative content production and

networking could be brought to a wider audience and serve as an

inspiration.

Interactive screens integrated into urban furniture

similar to a blackboard for comments, stories, conversations, could

also help to circulate and access data, serving and strengthening

the local community and its small-scale economy.

In 1997, Philips already was involved in a large research

project called LIME (Living Memory), which integrated

a local exchange platform into café tables and other urban

furniture. Following this early example, various projects aimed at

further developing the idea of interactive community boards and

supporting the information exchange in a local community are

currently being produced. [9]

In an attempt to address issues of fear in urban spaces,

Rude Architecture implemented a network of Chat Stops equipped

with interactive video technology, enabling communication between

people waiting at different bus stops. If they desired, people could

start a "video conference" with others waiting

somewhere else. By means of communication with other

inhabitants, the boredom of waiting could be alleviated through

conversations, and subjective feelings of safety could potentially be

increased. The project applies video communication instead of

video surveillance – voluntarily and transparent, but at the

same time entertaining.

The mobile phone can also be utilized as information

transmitter. Various artists have rediscovered the idea of the urban

dialogue in the form of speaker's corners and have been

experimenting with the use of SMS for public expression. The

project Storyboard by Stefhan Caddick used a mobile

Variable Message Sign situated in public space to display submitted

SMS text. Will the next step be to connect the

"blogosphere" to Urban Screens? What strategies will

prevent misuse and encourage high-quality submissions?

Involving an urban audience in experiments requiring

participatory planning and making use of the participatory tools of

new media is a great challenge. Screens in public spaces could

function as mediation board between the community and the local

planning department and serve as a public display for the exchange

of ideas.

Jeanne van Heeswijk's project Face Your

World – which took place in Columbus, Ohio, in 2002

– gave children on a bus access to a multi-user computer

game allowing them to redesigning their communities as they

envisioned them. [Fig. 6] At three bus stops, the creations were

displayed on special screen sculptures presenting the results of the

game to the urban community. As van Heeswijk put it, "It's

about the way people look at the space around them. With

everything being privatized now, people don't view the community

as their own any more." [10] In this case, digital media were

utilized as interaction catalysts for the participation and

engagement of young people in a local community.

Figure 6. Face Your World: involving young

kids in community planning.

Conclusion

Content needs to be coordinated with new visions of how,

when, and in what specific locations screens can be integrated in

the urban landscape and its architecture. The balance between

content, location, and type of screen determines the success of the

interaction with the audience and prevents noise and visual

pollution. Furthermore, we need to understand how the growing

infrastructure of digital displays influences the perception of our

public spaces' visual sphere.

Whenever we integrate a medium into the city's public

space, we need to assume responsibilities regarding the

sustainability of our urban society. Public space is the glue that

holds urban society together. It is time to shape future directions of

the developing "screen world" in a sustainable manner.

It is time to develop more creative visions for alternative, socially

oriented content for various types of Urban Screens and to avoid a

focus on technology. Other forces than merely commercial interests

should drive the attempt to shape the future development of the

emergent "screen world." [11]

Mirjam Struppek

Urban Media Research, Berlin

http://www.interactionfield.de

struppek@interactionfield.de

References:

[1] W. Christ, "Public versus private Space," IRS

international symposium, Die europäische Stadt - ein

auslaufendes Modell? (Erkner bei Berlin, Germany, March

2000).

[2] S. McQuire, "The Politics of Public Space in the

Media City" in Urban Screens: Discovering the potential of

outdoor screens for urban society, First Monday Special Issue

#4 (February 2006), http://www.firstmonday.org

[3] Lev Manovich, "The Poetics of Augmented

Space" (2002),http://www.manovich.net/DOCS/augmented_spac

e.doc

[4] P. Virilio, "We may be entering an electronic

gothic era" in Architectural Design - Architects in

Cyberspace II, Vol. 68 No. 11 / 12 (Nov. / Dec. 1998), pp.

61-65.

[5] For a list of artistic screening events and initiatives

see http://www.urbanscreens.org

[6] S. Best, D. Kellner, The Postmodern

Turn (Guilford Press: New York, NY, 1997), p. 82.

[7] For a detailed description of these developed

categories see http://www.interactionfield.de

[8] L. Wallace, "Screenworld" in Material

media, artefacts from a digital age (2003), http://www.machinehunger.com.au/phd/pdf

?

[9] E. Churchill et al. "Multimedia fliers:

information sharing with digital community bulletin boards" in

Huysman, Marleen et al. (eds.) Communities and

technologies (Kluwer, B.V.: Deventer, 2003), pp. 97-

117.

[10] van Heeswijk cited in J. Gentile, "Exhibit to

unite community," The Lantern Issue 6/27/02,

Arts Section (2002), http://www.thelantern.com

[11] For a detailed article presenting various Urban

Screens projects, see M. Struppek, "The social potential of

Urban Screens" in Screens and the Social Landscape,

Visual Communication, Vol. 5, No. 2 (Sage Publications, June

2006), pp. 173-188.

|