|

Introduction:

The Computational Roots of Aesthetic

Interactivity:

"...when human atoms are knit into an organization in which they are used,

not in their full right as responsible beings, but as cogs and levers and rods,

it matters little that their raw material is flesh and blood. What is used as an

element of a machine is in fact an element in a machine." (Wiener, p. 185)

Interactive, telematic art is the

child of developments in cybernetics,

electrical engineering, mathematics,

and computer science;

arguably as much as it is the offspring

of art history. The predictions

and concerns of the pioneering scientists

that developed these fields

facilitated radical new potentials for

interactivity in artistic practice.

A decisive shift in the development

of computational technologies that is

of particular importance to art

occurred with the July 1945 publication

of the essay "As We May

Think" by Vannevar Bush. Bush

was an electrical engineer, Dean of

MIT, and responsible for the development

and administration of

DARPA and the Manhattan Project.

In "As We May Think," he made

many suggestions in an effort to

facilitate the redirection of post-war

agendas in scientific research, but

most notably was his charge that

research in computational systems

shifts from replacing human workers

with computers to building machines

to augment individual human intellect.

The latter involved giving individual users an interface to access

the inner workings of the computer,

allowing for real-time sorting and

contact with data, and forming cross-referenced,

associative paths and

patterns. Bush coined the term

Memex to describe his proposed

associative data handling technique,

the precursor to Hypertext twenty

years later. This concept of a human-centered

agenda in computing was a

radical one in government-sponsored

research, especially after years of

war.

In the 1960s, the visionary scientists

J. P. L. Licklider and Douglas

Engelbart, inspired by Memex, began

to work toward the realization of a

human-centered, intelligence-augmenting

research model for computers.

In 1960, Licklider formulated a

research agenda based on the idea of

a symbiosis between humans and

computers, and later, in 1964, in his

publication "The Computer as a

Communication Device," set an agenda

for interactivity as mutual action

between humans and digital computers,

for the purpose of human communication,

creativity, and transcendence:

|

Vannevar Bush's theoretical

Memex machine,1945

Our emphasis on people is deliberate... We want to emphasize

something beyond one-way transfer: the increasing

significance of the jointly constructive, the mutually reinforcing

aspect of communication

- the part that

transcends... When minds

interact, new ideas

emerge. We want to talk

about the creative aspect

of communication.

Our emphasis on people is deliberate... We want to emphasize

something beyond one-way transfer: the increasing

significance of the jointly constructive, the mutually reinforcing

aspect of communication

- the part that

transcends... When minds

interact, new ideas

emerge. We want to talk

about the creative aspect

of communication.

|

|

As early as 1962, Douglas Engelbart

realized the potentials of the computer

as an intelligence-augmenting

device, and wrote of using the computer

for the development and augmentation

of "mental and cognitive

structuring in the human." (Engelbart,

p. 10)

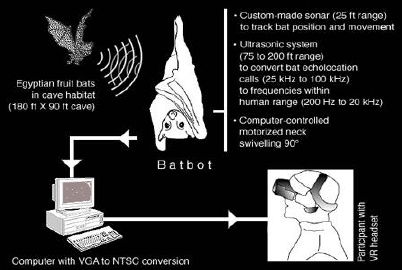

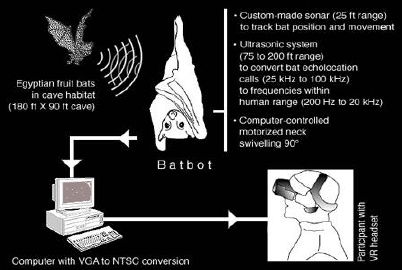

Diagram of Darker Than Night

Eduardo Kac,1999

In the late 1960s, Louis Fein, in making

a comprehensive projection of the

growth and dynamic inter-relatedness

of "computer-related sciences,"

includes specific mention of the

enhancement of human intellect by

the cooperative activity of men, mechanisms,

and automata. He profoundly expanded the range of interactivity

when he coined the term "synnoetics"

to describe the cooperative interaction

of people, mechanisms, plant or

animal organisms, and automata into

a system the mental power of which is

greater than that of its components.

Fein described synnoetics as a

"meta-discipline" arising out of the

symbiosis between people, machines,

automata, and other life forms, and

believed that it should be an academic

subject taught in an integrated

fashion. Synnoetics predicts the current development of biological, genetic,

and transgenic art forms currently

under development by artists like

Vibeke Sorensen, Eduardo Kac, and

Tiffany Holmes.

In the late 1960s, Louis Fein, in making

a comprehensive projection of the

growth and dynamic inter-relatedness

of "computer-related sciences,"

includes specific mention of the

enhancement of human intellect by

the cooperative activity of men, mechanisms,

and automata. He profoundly expanded the range of interactivity

when he coined the term "synnoetics"

to describe the cooperative interaction

of people, mechanisms, plant or

animal organisms, and automata into

a system the mental power of which is

greater than that of its components.

Fein described synnoetics as a

"meta-discipline" arising out of the

symbiosis between people, machines,

automata, and other life forms, and

believed that it should be an academic

subject taught in an integrated

fashion. Synnoetics predicts the current development of biological, genetic,

and transgenic art forms currently

under development by artists like

Vibeke Sorensen, Eduardo Kac, and

Tiffany Holmes.

The post-war agendas set out by

Bush, Licklider, Engelbart, and Fein

emphasize the evolution of the human

as the central force in cybernetics,

engineering, and computer science.

Their research forms a clear set of

criteria for the creation of aesthetic,

interactive context creation that is

human-centered. The issues vital to

an aesthetics of interactivity emerging

from their work are the following:

The research and development of

human/machine symbiotic models for

interactivity focus on the augmentation

of the human subject.

The synnoesis between

human/machine/environment emphasizes

a model of mutual exchange

between interacting minds, for the

purpose of emergence and transcendence.

Mutually interactive systems can facilitate

the development of new patterns

of cognition in people, thus confirming

a dynamic of mutual (ex)change. In

the process, the computer is construct -

ed as a dynamically integrated partner

in an associative synnoetic exchange;

an interaction that augments human

communication, creativity, transcendence,

and intelligence.

These scientists mapped a path for

the development of human/computational

interactivity that solidly places at

the center the creation of a symbiotic

or synnoetic, distributed "mind" whose

powers of human realization and transcendence

are greater than the sum of

its parts. After nearly 40 years of

speculation and development in interactive

art, a critical look at the genre

through this synnoetic lens could help

define future paths in the genre.

"How was it for you?"

Interactive Art in

Practice - 1965-Present:

The traditional static, contemplative

art object has now, in the human-centered

synnoetic-interactive paradigm,

become a dynamic, responsive

engine able to instantaneously tailor

its processes and outcome to a

unique dataset of choices and actions

signified by each individual entering

the input field of the aesthetic experience.

In the words of visionary 'interactive

artist,' theorist, and teacher Roy

Ascott:

The emerging new order of art is

that of interactivity, or "dispersed

authorship." The canon is one of

contingency and uncertainty… The

culturally dominate "objet d'art" as

the sole focus... is replaced by the

interface... The focus of the aesthetic

shifts from the observed object

to the participating

subject… (Ascott, p. 243)

Ascott brought to bear on art the theories

and concerns of Licklider and

Engelbart, especially with regard to

"the creative aspect of communication,"

as early as 1966 when he developed

his model for a "cybernetic art

matrix" that functions as a

tool for the mind,

an instrument for

the magnification

of thought, potentially

an intelligence

amplifier...

[T]he interaction of

artefact and computer

in the context

of the behavioural

structure, is equally

foreseeable...

The computer may

be linked to an artwork

and the artwork

may in some sense be a computer.

To understand this "aesthetic shift

from the observed object to the

participating subject," it is necessary

to examine the observed object

(static works of art) through the lens

of the aesthetics of synnoeisis, as

defined above. According to

Webster's Second International

Dictionary, there are two basic conditions

definitive of interactivity:

(1) that interaction implies mutual

acts, and (2), that action does not

necessarily imply a physical act but

can be an effect, suggestion, or representation.

(Webster's) Relative to

the second definition, implied or suggested

action is frequently a property

of traditional physically static forms

like painting and sculpture. Action

can simply be suggested and/or represented

and still reciprocate within

an active dialogue with a viewer

through the suggestion/representation

of action, or through the stimulation of

a reaction in the internal psychic life

or physiological behavior of the participant.

Media theorist Lev Manovich,

in his essay "On Totalitarian

Interactivity (notes from the enemy of

the people)," maintains that classical

and modern art were already

interactive in that they prompted a

viewer to

fill in missing information (for

instance, ellipses in literary narration;

"missing" parts of objects in

modernist painting) as well as to

move his / her eyes (composition in

painting and cinema) or the whole

body (in experiencing sculpture

and architecture). (Manovich,

1996)

Manovich further contends that, compared

to earlier genres, electronic

media often takes an entirely literal

attitude toward interactivity:

equating it (interactivity) with

strictly physical interaction

between a user and an artwork

(pressing a button), at the sake of

psychological interaction. The psychological

processes of filling-in,

hypothesis forming, recall and

identification -- which are required

for us to comprehend any text or

image at all -- are mistakenly identified

strictly with an objectively

existing structure of interactive

links. (Manovich, 1996 )

Manovich and others clearly argue

that all works of art can be described

as interactive, because there always

has been a "reciprocal action," or

feedback condition between the art

object and the viewer. The static

work depicts action, the viewer

responds.

However, the first definition cited

above that interaction implies mutual

acts, is a definitive criterion for interactivity

that eludes the traditional relationship

between static works and

their viewers. This aspect of mutual

action was central to the research

models proposed by Bush, Licklider,

Engelbart and Fein and undermines

Manovich's contention that all works

of art can be described as interactive.

Although one can obviously argue

that the static work of art does act

upon the viewer in a number of very

profound ways, one would be hard

pressed to say that the action is mutual

or reciprocal. The range of physiological,

emotional, spiritual, political,

humanist, psychological, and moral

ideologies impressed upon the viewer

by artists through their work is at the

core of the power of static art; however,

the viewer's actions and will in the

presence of a static work do not

change anything about the physical

structure or corporeal nature of the

object itself. According to this definition,

the aesthetic experience with a

static work of art can be called active,

but not interactive.

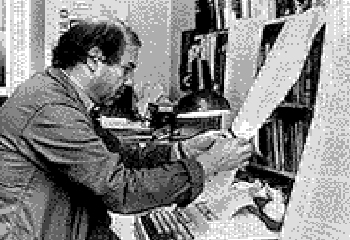

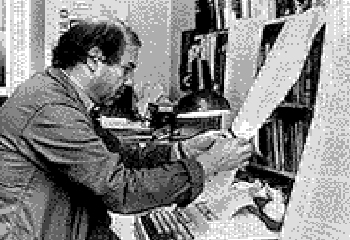

Roy Ascott, 1983, working at the TI-745

terminal/printer (Photo: Electra catalogue)

In practice much of the digital work

called interactive offers a very limited

degree of participation as the interactor is confined to basic levels of button-pushing, call and response structures, and prescribed alternatives

within a fixed whole. Ascott's canon

of "contingency and uncertainty" is

often an illusion created by the interface,

masking a logic requiring hardcoded

certainty and order. These

works unintentionally reveal that traditional

print media can offer the same

possibilities of non-linear, random-access

reading as do many CD-ROMs

and websites, albeit with

greater accessibility, stability and

compatibility. In addition, the "interactor's" physical action of pushing a button

or triggering a sensor frequently

seems only related to the consequence

or signification of her action in

a purely literal way, that is, push button,

something occurs. Many interactive

artworks are machine-centered,

both in terms of the interface and the

nature of interaction, while simultaneously

surrounded by a body of discourse

and expectation denying that

this is so. The initial prototype of

"First Order Cybernetics," the feedback

loop, is the model for such interactive,

electronic artworks. The feedback loop is a process frequently

found in machines intended to maintain

a particular state or pattern, like a

governor or thermostat. A simple

feedback loop is analogous to a

closed system of interaction in

Manovich's definition. In closed systems,

we can attribute no intelligence

to the interface, it does not learn from

the action of the environment, simply

leads the participant down an

unchanging branching structure or

pattern of motion, offering pre-rendered

elements or pre-programmed

responses. The individual interactor

is not permitted to follow, in Bush's

terms, an "associative trail." The path

is a pattern, repeatable, and the result

predictable, the internal purpose is the

maintenance of a homeostatic condition

for the machine. In the case of

many interactive pieces, the initial pattern

of machine logic conditions the

interactor's behavior to keep the piece

up and running.

In practice much of the digital work

called interactive offers a very limited

degree of participation as the interactor is confined to basic levels of button-pushing, call and response structures, and prescribed alternatives

within a fixed whole. Ascott's canon

of "contingency and uncertainty" is

often an illusion created by the interface,

masking a logic requiring hardcoded

certainty and order. These

works unintentionally reveal that traditional

print media can offer the same

possibilities of non-linear, random-access

reading as do many CD-ROMs

and websites, albeit with

greater accessibility, stability and

compatibility. In addition, the "interactor's" physical action of pushing a button

or triggering a sensor frequently

seems only related to the consequence

or signification of her action in

a purely literal way, that is, push button,

something occurs. Many interactive

artworks are machine-centered,

both in terms of the interface and the

nature of interaction, while simultaneously

surrounded by a body of discourse

and expectation denying that

this is so. The initial prototype of

"First Order Cybernetics," the feedback

loop, is the model for such interactive,

electronic artworks. The feedback loop is a process frequently

found in machines intended to maintain

a particular state or pattern, like a

governor or thermostat. A simple

feedback loop is analogous to a

closed system of interaction in

Manovich's definition. In closed systems,

we can attribute no intelligence

to the interface, it does not learn from

the action of the environment, simply

leads the participant down an

unchanging branching structure or

pattern of motion, offering pre-rendered

elements or pre-programmed

responses. The individual interactor

is not permitted to follow, in Bush's

terms, an "associative trail." The path

is a pattern, repeatable, and the result

predictable, the internal purpose is the

maintenance of a homeostatic condition

for the machine. In the case of

many interactive pieces, the initial pattern

of machine logic conditions the

interactor's behavior to keep the piece

up and running.

The greatest failure of

such works is that too

often the interactor is

manipulated by the cybernetic

system into believing

that the thought trajectory

they are developing

is their own. The

inevitable realization that

it is both the artist's

thought trajectory and the

conditions of the computational

system they are

following leaves many

viewers with a feeling of

detachment and deception.

Manovich describes this experience:

Now, with interactive media, instead

of looking at a painting and mentally

following our own private associations

to other images, memories,

ideas, we are asked to click on the

image on the screen in order to go

to another image on the screen,

and so on. Thus we are asked to

follow pre-programmed, objectively

existing associations. In short, in

what can be read as a new updated

version of Althusser's "interpolation,"

we are asked to mistake the

structure of somebody else's mind

for our own. (Manovich, p. 61)

Such efforts in interactive art can be

said to actually curtail the participant's

range of free association while simultaneously

espousing assumptions

based in democratic and utopian

ideals of open process and distributed

authorship. Human aesthetic, emotional

and sentient experience is constructed

in terms of the logic of the

machine, rather than, as the developers

of interactivity called for, the other

way around. The goals of interactivity

as previously outlined above by Bush

et al. - human centeredness, associative

paths, mutual action, cognitive

mapping, and by Ascott - undecidability,

potentiality, immateriality, transformation,

mutability - are frequently at

odds with the goals of machine maintenance

and homeostasis.

This is certainly not to say that the

enterprise of interactive art has been

a failed project. Indeed, there have

been works by a number of artists,

Roy Ascott probably being the first,

that exploit the defining agendas of

human-centered, symbiotic interactive

systems to create powerful new

aesthetic contexts. It would seem

that, as digital systems become more

powerful and ubiquitous, the number

of effective works would increase

incrementally, but in my judgment this

is not the case.

If an interactive artwork stops running

before it should, as they frequently

do, then all is lost; but if the cybernetic

system is conceived of as a work

of art, then the facilitation and augmentation

of the aesthetic experience

in the human subject should prevail.

There are a number of issues that

make the maintenance of a human-centered,

cybernetic paradigm a very

difficult task. Whether considering

the aesthetic experience with regard

to the "objet d'art" or the interface, it

is not difficult to analyze and construct

numerous theorems concerning

the composition, structure, and

technology of what Engelbart called

"the explicit-artifact," that is, the work

of computational work of art. What

remains illusive is the nature of the

internal experience of the human

subject when in dialogue with these

artifacts. How is the human affected,

how do we know if the "explicit

human" has changed? As, according to Licklider, mutual exchange is

an optimum condition of symbiotic

interaction, an understanding of the

dynamic, qualitative experience of the

person is necessary in order to contribute

to the production of optimal

aesthetic experiences within interactive

interfaces.

Distributed Minds,

Biometrics, Cognitive

Remapping, and Psi Phenomena:

In 1954, Norbert Wiener wrote, in

"The Human Use of Human Beings,

Cybernetics and Society":

|

But while the universe as a whole, if indeed there is a whole universe,

tends to run down, there are local enclaves whose direction seems

opposed to that of the universe at large and in which there is a limited and

temporary tendency for organization to increase. Life finds its home in

some of these enclaves.

(Wiener, p. 12) |

|

There are enclaves of cybernetic

activities, some within the conventional

canons, and some at the

fringes or entirely outside the realms

of acceptable art or science that shed

light into the mysteries of dynamic

human subjectivity.

Distributed Mind:

Roy Ascott began exploring concepts

of "distributed mind" and creative

communication networks in his cybernetic

experiments in education and

art in the early 1960s. He created

many interactive works in the 1960s

and 70s where "participators" were

able to shape the current state of a

given work. His model for the "cybernetic

art matrix" finally came to fruitition

in 1983 with the exhibition of his

"La Plissure du Texte" at the Musée

de l'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris.

Edward Shanken, In "Telematic

Embrace: A Love Story? Roy

Ascott's Theories of Telematic Art,"

offers the following description of this

seminal work:

Roy Ascott's La Plissure du Texte, 1983

Roy Ascott's La Plissure du Texte

(The Pleating of the Text), 1983, was

identified by Leonardo editor Roger

Malina as an unsurpassed landmark

in the history of Telematic Art. This

work explored the potential of computer

networking for interactive creative

exchange between remote participators,

first theorized by Ascott

in 1966. The project was produced

as part of the Electra exhibition organized

in 1983 by art historian

Frank Popper at the Musée de l'Art

Moderne de la Ville de Paris. La

Plissure du Texte allowed Ascott and

his collaborators at eleven locations

in the US, Canada, Europe, and Australia

to experiment with what the artist

has termed "distributed authorship."

Each remote location represented

a character in the "planetary

fairytale," and participated in collectively

creating and contributing texts

and ASCII-based images to the interactive

unfolding, or distributed

authorship, of the emerging story.

Artist Hank Bull, who participated

in the event from the Vancouver

node described "the result of this intense

exchange" as a "fat tome of

Joycean pretensions that delved

deep into the poetics of disembodied

collaboration and weightless

network rambling." (Shanken, 2001)

Ascott's work clearly pre-dates the

internet, net art, MUDs and MOOs

and is a profound realization of a distributed

realization of Vannevar

Bush's Memex. Anecdotal accounts

from the artists that participated in

"La Plissure du Texte" indicate qualitatively

that their interaction was a

profound experience, free associative,

surreal, and full of unforeseen

narrative twists. It must be pointed

out however, that - unlike many

of Ascott's analogue works of the

60s and 70s - visitors to the exhibition

in Paris were involved primarily

as spectators immersed in a textual

space, unable to affect the direction

of the work.

Biometrics and

Cognitive Mapping:

Doug Engelbart's belief that interactive

systems could change cognitive

structures in human participants finds

its fruition in the growing number of

interactive artworks involving real-time

biometric data flows. The use of biometrics,

especially biofeedback, as a

method of interacting with aesthetic

interfaces, dates back to Jean Millay's

Stereo Brainwave Biofeedback Light

Sculpture of 1971. The interface was

based in R. Timothy Scully's portable

Aquarius Electronics Alphaphone™, a

brainwave analyzer that sorted brainwave

frequencies into sound signals.

John Millay's Brainwave Light Sculpture, 1971

The Stereo Brainwave

Biofeedback Light Sculpture

changes its colors and patterns

with changes in thoughts…

Mandela patterns are used so the

visual focus is not distracted when

the lights change… the feedback

tones accompanied feelings of

deep meditation… I wondered if it

would be possible for two people

to learn to synchronize their brainwaves

to improve telepathic communication.

(Millay, p. 9)

Millay has continued to pursue the

question of the use of biofeedback to

improve telepathic communications in

her subsequent experiments in

remote viewing, forging agendas set

forth by Licklider (creative communication,

interaction of minds),

Engelbart (cognitive structuring), and

Bush (intercepting brain transmissions).

An on-going project, "The Meditation

Chamber," being developed by Chris

Shaw, Larry Hodges and Diane

Gromala at the Georgia Institute of

Technology, is a virtual reality-based

program that uses biofeedback to

facilitate meditative states through

video and audio guidance:

Users wear a head-mounted display

with audio and video that

guides them through a series of

sunset and moonrise scenes and

muscle relaxation exercises. The

system also monitors the users'

respiration, pulse rate and sweat

gland activity (a measure of calmness)

to provide real-time biofeedback

regarding the effectiveness of

the virtual experience. (Gromala,

Hodges, and Shaw)

"The Meditation Chamber" augments

individual users abilities

for visualization, a necessary

component to success in the

use of meditation as a healing

therapy.

In Darij Kreuh and Davide

Grassi's "Brainscore:

Incorporeal Communication,"

biofeedback devices and eyetrackers

are used in a virtual

reality performance environment.

The biometric devices

allow two performers to control virtual

avatars projected for an audience in

stereo on a large screen. The stated

aim of "Brainscore" is

to create a controlled flow of information

in terms of audio-visual

messages in order to establish

communication with the audience.

(Grassi and Kreuh)

Darij Kreuh and Davide

Grassi's Brainscore, 2000

"Brainscore" was first

performed in the Cultural

and Congress Centre in

Ljubljana, Slovenia, in

September of 2000 and

continues to tour. Kreuh

and Grassi contend that

"Brainscore" offers their

audience a completely new

point of view, "leading the

audience to perceive a concrete

co-existence (as a

kind of promiscuous copenetration)

of two Realities at the

same time." (Grassi and Kreuh)

"Brainscore" was first

performed in the Cultural

and Congress Centre in

Ljubljana, Slovenia, in

September of 2000 and

continues to tour. Kreuh

and Grassi contend that

"Brainscore" offers their

audience a completely new

point of view, "leading the

audience to perceive a concrete

co-existence (as a

kind of promiscuous copenetration)

of two Realities at the

same time." (Grassi and Kreuh)

In each of these pieces, the biometric

interface sets up a reflexive cybernetic

loop where the human's output, in the

form of electronic impulses, alters the

machine's output of images, motion,

and sound. In turn, the output of the

machine, as sensory stimulas,

becomes the new condition of input

for the human subjects. "Brainscore"

creates a larger, telematic loop in that

it brings an audience into the reflexive

process. The response the human

subject receives in biofeedback is an

indication of internal dynamics related

to emotional or involuntary systems of

the human's body. Biofeedback

encounters, like the use of virtual

environments in phobia treatment

(Hodges), have proven effective in

creating new relationships to physiological

and psychological conditions in

human subjects through the process

of cognitive remapping in the mind

and body of the interactor. Clearly, in

these interactive artworks Engelbart's

goals related to the augmentation of

mental and cognitive structuring in the

human brain are occuring. It is clear

that technologically mediated works of

art that employ biofeedback interfaces

can facilitate mutually interactive,

quantifiable states in which all the elements

of the cybernetic system - the

human, the machine, and the information

- are in a contingent state of

dynamic, reciprocal change.

Art/Psi Phenomena:

Must we always transform to

mechanical movements in order to

proceed from one electrical phenomenon

to another? Might not

these currents be intercepted,

either in the original form in

which information is conveyed to

the brain, or in the marvelously

metamorphosed form in which

they then proceed to the hand?"

(Bush, p. 107)

Danish artists Christian Skeel and

Morten Skriver, in partnership with

PEAR (The Princeton Engineering

Anomalies Research Laboratory)

have built and installed "The Trapholt

Experiment" at the Trapholt Museum

for Moderne Kunst in Denmark in

March 3, 2001. The one-year-long

installation is designed to determine

whether human consciousness is

capable of interacting with and affecting a microprocessor. The installation

consists of a custom computer that

generates a random sequence of

numbers, and of a computer monitor.

The monitor hangs on a wall in a small

room; the computer is entirely hidden

from view. The monitor displays an

image that constantly changes from a

depiction of a newborn child to white

noise. The random number generator determines second by second

whether a given pixel is part of the

image of the child or part of the white

noise. The system documents its

decisions in real time and is

extremely accurate. The laws of

probability state that in this random

system, the image of the child will be

visible 50% of the time. The monitor

is the only interface, there are no

additional sensors or input devices.

Danish artists Christian Skeel and

Morten Skriver, in partnership with

PEAR (The Princeton Engineering

Anomalies Research Laboratory)

have built and installed "The Trapholt

Experiment" at the Trapholt Museum

for Moderne Kunst in Denmark in

March 3, 2001. The one-year-long

installation is designed to determine

whether human consciousness is

capable of interacting with and affecting a microprocessor. The installation

consists of a custom computer that

generates a random sequence of

numbers, and of a computer monitor.

The monitor hangs on a wall in a small

room; the computer is entirely hidden

from view. The monitor displays an

image that constantly changes from a

depiction of a newborn child to white

noise. The random number generator determines second by second

whether a given pixel is part of the

image of the child or part of the white

noise. The system documents its

decisions in real time and is

extremely accurate. The laws of

probability state that in this random

system, the image of the child will be

visible 50% of the time. The monitor

is the only interface, there are no

additional sensors or input devices.

|

If the results of the Trapholt Experiment correspond

to those arrived at by the PEAR

Laboratory during the previous twenty years of

research, they will be yet further indication that

consciousness is not a phenomenon limited to

the human brain but one that can transcend

physical limits, with the potential to interact with

anything in the world. (Skeel and Skriver)

|

This experiment is the first work of

art that attempts to document and

measure psi phenomena. Psi

research began in earnest in the

1880s through a series of experiments

started by the British physicist

Sir William Barrett. Psi phenomena

are defined as interactions between

organisms and their environment, or

the environment and organisms, in

which it appears that information has

been passed, or that an influence

has occurred that cannot be understood

by conventional scientific

explanations of communications and

sensorial channels. (Radin, 1997)

The research has shown that man is

capable of using his consciousness

to affect these systems to a slight

but nevertheless decisive degree.

The research also seems to indicate

that the effect works differently with

groups than individuals, backwards

and forward in time, and over great

geographical distances. "The

Trapholt Experiment" cleverly

exploits a basic human desire to see

life and order rather than death and

chaos, and sets out to measure

whether our innate will for survival

can influence our environment.

Although this work does not seem to

participate in a system of mutual

interaction, as outlined by Licklider, it

is of great importance. This

research may represent a fourth

stage in the development of cybernetics,

as it introduces an entirely

new channel for information

exchange and communication

between humans and machines.

The "Trapholt Experiment" uses

technology in a profound and innovative

way, not to augment or

extend human consciousness, but

to measure the extent to which the

boundaries of human consciousness

are not known. In Psi phenomena,

consciousness only needs amplification

to be measured, thus consciousness

augments technology,

not the other way round. Psi phenomena as a form of wireless communication

may be of profound

importance to the future development

of interactive, synnoetic interfaces,

augmented, distributed minds,

as well as to a new, undefined context

for aesthetic experience.

What is important to an understanding

of how interactivity in art can

meet its full potential is the shift from

what N. Katherine Hayles describes

as a focus on the silicon/information

transfer side of the interactive equation

to a focus on the poetic evolution

of the human subject. One

could argue that this factor, poetic

evolution, is the most important criterion

for success in a work of art.

The need for human focus comes

into high relief in technologically

mediated artworks, as the technological

demands to maintain

machine homeostatis are so great,

and because information appears to

have "lost its body." In the case of

distributed, biometric and anomalous

interactivities, information spirals

through the cybernetic exchange,

from organic to the inorganic and

back, while remaining grounded in

human intentionality and perception.

The grounding of information in the

human will-to-consciousness gives

information back its body, and re-orients

the focus of cybernetic discourse.

The question becomes how

can the human will-to-consciousness

extend our technological systems,

not how can technology be a vehicle

for consciousness. Experiments cojoining

late stage cybernetics,

human biometrics, psi phenomena,

and aesthetic interactivity represent

a new vehicle for the evolution of

human sentience that conditions a

new outcome, or object of inquiry.

This new condition is neither art nor

science, but a cumulative transformation

of the discourses of both; a

transformation that celebrates

human connectivity and the will to

survive.

Although this work does not seem to

participate in a system of mutual

interaction, as outlined by Licklider, it

is of great importance. This

research may represent a fourth

stage in the development of cybernetics,

as it introduces an entirely

new channel for information

exchange and communication

between humans and machines.

The "Trapholt Experiment" uses

technology in a profound and innovative

way, not to augment or

extend human consciousness, but

to measure the extent to which the

boundaries of human consciousness

are not known. In Psi phenomena,

consciousness only needs amplification

to be measured, thus consciousness

augments technology,

not the other way round. Psi phenomena as a form of wireless communication

may be of profound

importance to the future development

of interactive, synnoetic interfaces,

augmented, distributed minds,

as well as to a new, undefined context

for aesthetic experience.

What is important to an understanding

of how interactivity in art can

meet its full potential is the shift from

what N. Katherine Hayles describes

as a focus on the silicon/information

transfer side of the interactive equation

to a focus on the poetic evolution

of the human subject. One

could argue that this factor, poetic

evolution, is the most important criterion

for success in a work of art.

The need for human focus comes

into high relief in technologically

mediated artworks, as the technological

demands to maintain

machine homeostatis are so great,

and because information appears to

have "lost its body." In the case of

distributed, biometric and anomalous

interactivities, information spirals

through the cybernetic exchange,

from organic to the inorganic and

back, while remaining grounded in

human intentionality and perception.

The grounding of information in the

human will-to-consciousness gives

information back its body, and re-orients

the focus of cybernetic discourse.

The question becomes how

can the human will-to-consciousness

extend our technological systems,

not how can technology be a vehicle

for consciousness. Experiments cojoining

late stage cybernetics,

human biometrics, psi phenomena,

and aesthetic interactivity represent

a new vehicle for the evolution of

human sentience that conditions a

new outcome, or object of inquiry.

This new condition is neither art nor

science, but a cumulative transformation

of the discourses of both; a

transformation that celebrates

human connectivity and the will to

survive.

WORKS CITED:

Ascott, Roy, "Is There Love in the

Telematic Embrace?", Art Journal,

49:3 (Fall 1990)

Bush, Vannevar. "As We May

Think," The Atlantic Monthly,

Volume 176 No. 1 (July 1945),

pp. 101-108.

Engelbart, Douglas C.

"Augmenting Human Intellect: A

Conceptual Framework." Summary

Report AFOSR-3223 under

Contract AF 49(638)-1024, SRI

Project 3578 for Air Force Office of

Scientific Research, Stanford

Research Institute, Menlo Park,

Ca., October 1962.

Grassi, Davide and Darij Kreuh,

"Brainscore--incorporeal communication,"

http://www.brainscore.org/

Gromala, Diane, Hodges, Larry

and Shaw, Christopher, "The

Meditation Chamber," GVU Center,

Georgia Institute of Technology, http://www.gvu.gatech.edu/gvu/meditation/proj_frameset.htm

Hayles, N. Katherine, How we

Became Posthuman (The

University of Chicago Press:

Chicago / London, 1999)

Licklider, J. C. R, "The Computer

as a Communication Device,"

reprinted from Science and

Technology (April 1968)

Manovich, Lev, The Language of

New Media (MIT Press, Leonardo

Books: Cambridge, MA, 2001)

Manovich, Lev "On Totalitarian

Interactivity (notes from the enemy

of the people)"

http://www.manovich.net/text/totalitarian.html (1996)

Millay, Jean, Multidimensional

Mind: Remote Viewing in

Hyperspace, A Universal

Dialogues Book (North Atlantic

Books: Berkeley, CA, 1999)

Shanken, Edward A. "Telematic

Embrace: A Love Story? Roy

Ascott's Theories of Telematic Art,"

Telematic Connections Timeline,

http://telematic.walkerart.org/timeline/timeline_shanken.html#

Radin, Dean, The Conscious Universe: The Scientific Truth of Psychic Phenomena

(HarperEdge: New York, 1997)

Skeel and Skriver, "Trapholt

Eksperimentet," Sensualogic.org,

http://www.sensuallogic.org/Members/skeel/category_1019984899/frameset.html

Wiener, Norbert, The Human Use

of Human Beings: Cybernetics

and Society (Doubleday Anchor

Books: Garden City, NY, 1954)

|